- Home

- >

- Content Pages

- >

- Technical Resources

- >

- Pestology Blog Entries

- >

- H5N1 Virus Transmission, German Cockroach Control Tools, and Bed Bugs

Pestology Blog

H5N1 Virus Transmission, German Cockroach Control Tools, and Bed Bugs

Fairfax, VA – January 1, 2026

The team kicks off the new year covering new research on the role pests play in spreading H5N1 virus, how German cockroaches respond to commercial essential oils, and new data on thermal thresholds for the common bed bug. We're joined by special guest Faye Golden of Cook's Pest Control!

Featured Article Summaries

H5N1 Virus Transmission

Ecology and Spread of the North American H5N1 Epizoonotic

Understanding the ways that we prevent disease is important in our line of work. But, much like understanding the biology and behavior of the pest can contribute to the success of your management strategy, understanding the ways disease can spread can be just as important when discussing prevention.

H5N1, more commonly known Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza recently came to the forefront in North America in 2024 as it quickly spread through not only poultry farms and dairy farms, but also featured at least 71 human cases in the United States as well. The researchers of this paper sought to understand how this strain of avian influenza spread across North America. They did so by taking data from positive samples collected by USDA APHIS across November 2021-September 2023 and examined the genomes of the positive viral samples from domestic birds, wild birds, and mammals. Specifically, the researchers compared the DNA make-up of the protein hemagglutinin in these samples. By comparing the DNA that codes from the protein hemagglutinin, the researchers could trace the path of how and when this virus likely spread by tracking those changes to the genetic make-up of the protein over time. Hemagglutinin is a great candidate for examining how a virus spreads as it is the first protein that binds with a host’s red blood cells and represents the first step in the infection process. By using this genetic backtracking known as viral phylodynamics, researchers can understand and pinpoint how and why these outbreaks occur- and more importantly, where these viruses may go next.

Photo Credit: NIAID

First, most of the North American sequences they examined descended from a single introduction that was likely from migratory gulls coming in from Europe in late 2021. However, they were also able to track additional introductions from both Asia and Europe for an estimated total of at least nine introductions across 2021-2023. Repeated introductions mean a larger opportunity for this virus to spread across populations.

Similarly, the researchers were also able to document similar genetic strains of the virus across the four migratory pathways across North America. This suggests that not only can we track the potential movement of the virus, but we can also show that these wild migratory bird pathways are extremely important in the dissemination of the virus. This is also supported by the fact that case detections of avian influenza peaked in the fall and the spring, which coincides with migration timing. In terms of the main suspects and drivers of this viral spread a-la-migration, unsurprisingly the order Anseriformes were the main suspects. This order consists of the waterfowl, such as ducks, geese, swans, and others, and are known for their migratory patterns. However, in terms of spreading the virus to other species, shorebirds as well as the order Galliformes, which includes species like chickens, turkeys, pheasants, and quail were the top suspects.

As a result, documented outbreaks in domestic birds appeared to be driven by repeated introductions from wild birds, with the estimates suggesting that there were at least 106 introductions from wild birds into domestic birds, and 4 introductions from domestic birds to wild birds.

Lastly, the researchers examined the likelihood of “backyard birds” to become infected compared to commercial birds. With the increase in popularity in home-raised domesticated poultry, this becomes an important avenue to consider for infection of avian influenza from wild birds to domesticated birds. From examining the genetics of the positive samples collected, researchers were able to document not only that backyard birds were infected earlier on average compared to commercial birds, but also featured a higher variety of introductions, suggesting that they are encountering wild birds more than commercial birds.

Wild birds, particularly waterfowl, played an important role in the recent Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza outbreak. This group, along with commercial birds, are both groups that pest management professionals may encounter in their regular work. Therefore, understanding the ways in which a disease may spread through these groups can be the first line of defense in our role of protecting public health as well as the safety of our industry.

Article by Laura Rosenwald, BCE

References

Damodaran, L., Jaeger, A.S. & Moncla, L.H. Ecology and spread of the North American H5N1 epizootic. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09737-x

German Cockroach Control Tools

Behavioral Preference and Antennal Responses Induced by Commercial Essential Oil Formulations and Their Components in the German Cockroach (Blattodea: Ectobiidae)

It has become an increasing trend that customers are interested in the most all natural, environmentally friendly, “green” solutions to all their problems. Organic, all natural, no harsh chemicals”. These are all phrases that attract the eco conscious or highly medically sensitive individuals. There are also those in the camp of “give me the most lethal pesticide you legally can, I want scorched earth on these pests and no natural oil is gonna cut it.” Basically, you have varying customer attitudes towards pest management approaches.

This article began to explore that very conundrum. Do the essential oil-based pesticides cut it? Specifically, what kind of response do we see by pests to these compounds? This was not a paper looked at mortality experiments but rather the beginning phases of how pests react to compounds and oils commonly used in these products. The researchers used the German cockroach, one of the most common household pests known to be resistant to many insecticides. They used resistant and susceptible strains of the cockroaches and tested how they would respond to 6 different commercially available essential oil-based formulations.

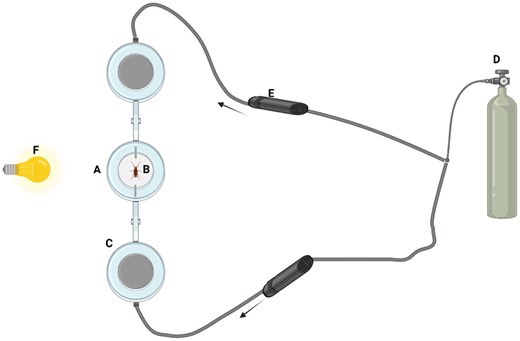

They made sure to choose formulations that were labelled for cockroaches. The first test they did was called an electroantennogram. The electroantennogram was connected as you might expect to the cockroach antennae and to probes that measured the electrical impulse response of the antennae to the stimulus. It’s important to note that we can’t tell if the response here was positive or negative just whether they were responding to the sensory input in some way.

The next thing they looked at was if the size of the antennae had anything to do with the response. Was a shorter or longer antennae responding differently? That was just a measurement analyzed at the end of the electroantennogram studies. And to cover that immediately, they found that the longer the antennae was, the stronger response to the stimulus.

The other major part of the investigation was olfactometer assays. An olfactometer has to do with scent and the whole cockroach reaction towards or away from the stimulus. You have a chamber with the cockroach and it gets pesticide tinted air from one side and it can choose to go towards or away from that. See figure below from the paper. They recorded the choices the cockroaches made when faced with the options.

Across all tests, there were some universal findings. Firstly, that a higher concentration of product lead to a greater response so greater electrical signals in the antennae and greater avoidance in the olfactometer chambers. This is pretty expected. Next, Essentria elicited the greatest response amongst all products specifically the component, menthone which is related to menthol was driving that response compared to other ingredients. Orange guard and Garsentria had the lowest response rates, and these were citrus or pine derived ingredients.

An interesting observation across the board was that the rate of product needed to elicit a strong negative response was often higher than the label listed rate of these products besides the Essentria. Meaning that while these products may be effective, they may not be effective at the label listed rate which means that they may not be effective in real world scenarios.

As with almost any research paper, the conclusions have the disclaimer that further research into these details is needed. Essential oil formulations are less likely to initiate resistance than other pesticides but some of them may need to up the label rates to elicit a stronger response. The proof here though does show that there are negative responses to the pesticide, it does repel the pests and has potential for wide usage but only in proper placement within a comprehensive IPM program.

Article by Ellie Sanders, BCE

References

Festus K Ajibefun, Ana M Chicas-Mosier, Henry Y Fadamiro, Arthur G Appel, Behavioral preference and antennal responses induced by commercial essential oil formulations and their components in the German cockroach (Blattodea: Ectobiidae), Journal of Economic Entomology, 2025;, toaf296, https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toaf296

Bed Bugs and Humidity

Determination of Temperature and Relative Humidity Combinations that are Lethal to Bed Bugs (Cimex lectularius)

Article by Mike Bentley, PhD, BCE

References

Listen to the Episode!

Have questions or feedback for the BugBytes team? Email us at training@pestworld.org, we'd love to hear from you!